Looking Back to Back to the Future Day…

21/11/2015

October 21st, 2015. The day Emmett “Doc” Brown and Marty McFly arrive in the future from 1985. Except now that is a month ago and the future they encounter(ed) – already an alternate timeline to us – has itself become history. Or at least historical fiction. It has got me thinking over the last few weeks about the franchise and about the life which stories like Back to the Future enjoy once their imagined future becomes out past. Because they endure in a way which I’m sure their creators could never have expected. Fans continue to cosplay as the characters. The original script – as structurally perfect a piece of screenwriting as you are every likely to find – is taught in film schools. Meanwhile the movies themselves return to the cinema again and again, delighting new audiences and new generations in ways which could never have been imagined thirty years ago.

As my friend Tiffani Angus said on Facebook last month, “How amazingly cool is it that Back to the Future, a movie franchise that didn’t win a best movie Oscar or a Golden Globe or anything huge like that, is so much a part of our lives – among the geeks and non-geeks – that we celebrate it for a whole day? And that we use this platform to do so, with people we likely didn’t even watch the movie with in the first place?”

***

“I guess you guys aren’t ready for that yet. But your kids are gonna love it.”

My first memory of the Back to the Future franchise was sometime in the very early 1990s. It was a Sunday and my father had brought me with him on a visit to a friend of his in the village where he had grown up (which is how I know it was a Sunday; that was always the day we paid a visit to that side of the county). I recall how the family we were visiting were watching Back to the Future II and we arrived during the dystopian, alternate-1985 part of the film. I wasn’t even ten years old at that point and I had no idea what was going on, no context for either the film itself or the franchise. A tank? What? Who is this guy with the bad hair?

I didn’t get it. I didn’t even like it (I wasn’t there long enough to see anything other than the stretch between the lawless Hill Valley sequences and the scenes in Biff’s Casino). But now, of course, Back to the Future II is easily my favourite film of the trilogy; one of my favourite films full stop, if I’m to be honest about it, and my own personal benchmark for entertaining time travel shenanigans.

It’s amazing the difference which a flying DeLorean will make.

***

“Last night, Darth Vader came down from Planet Vulcan and told me that if I didn’t take Lorraine out, that he’d melt my brain.”

Maybe it’s appropriate that my first exposure to a real time travel story was out of narrative order. It wasn’t until years later that I saw the original Back to the Future which – as mentioned – is one of the finest screenplays of all time (indeed, for me, the only film of the last thirty years which rivals it is 2007’s Hot Fuzz). I’ve seen it many, many times by now. I love it; not as much as I love Part II, mind (!), but it is definitive, isn’t it? For a whole generation, the original Back to the Future is how time travel works: you can drive your car down the street from one decade to another (which is to say the films don’t really address the spatial element of time travel); if you alter the past you risk slowly dissipating from reality; and, of course, pop culture is an inescapable aspect of life no matter the time period.

That said, I was on a time travel panel at Octocon in Dublin about six weeks ago and somehow – in retrospect this seems unforgivable! – I don’t think we ever mentioned Back to the Future. I corrected that yesterday when a Creative Writing class about narrative time became a group discussion about time travel (“technically relevant”, as one of the students put it!), about the challenges of telling such stories, and about the head-wrecking loops and possibilities which they present to a writer. We ended up talking about the effect of thinking too much about time travel might have on a person and I invoked the physicist David Deutsch, a “cloistered genius” whose home, according to one New Yorker profile, is:

“..Cluttered with old phone books, cardboard boxes, and piles of papers […] Taped onto the walls of Deutsch’s living room were a map of the world, a periodic table, a hand-drawn cartoon of Karl Popper, a poster of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, a taxonomy of animals, a taxonomy of the characters in The Simpsons, colour printouts of pictures of McCain and Obama, with handwritten labels reading ‘this one’ and ‘that one,’ […] There were also old VHS tapes, an unused fireplace, [and] a stationary exercise bike…”

Certainly the similarities between Deutsch’s home and that of Doc Brown were not lost on the students.

***

“I cautioned you about disrupting the continuum for your own personal benefit.”

Nowadays the only thing I don’t like about BTTF II it is the trailer for Part III tagged on rather inelegantly to the final moments of it. Any time I am rewatching it, I make a point of stopping the film before that rolls because, for me at least, the trailer ruins one of my favourite film endings of all time.

That’s my way of admitting that I’ve never enjoyed Back to the Future III as much as the other two (I don’t even think I enjoy the western version of the BTTF theme music!). I suspect that it is because it never feels as urgent or as connected to the character of Marty as parts I and II. Structurally (and, again, this was something we spoke about in class yesterday) it fails to interlock with what came before in as satisfying a fashion as Part II does. Because while it has some fun moments for sure (the photograph with the clock, in particular), and no doubt many people rank it highly, for me it feels thematically disconnected from the universe of the first two films.

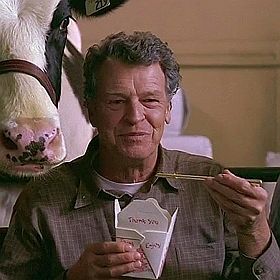

Maybe it is heresy to say (!), but I think this is because Doc is the protagonist here rather than Marty. Think of the diagram on the chalkboard in Part II and the symmetry of the 30 year-long jumps back and forwards from the 1980s in the first two films, jumps which allow Marty to explore the lives of his parents and his children in turn. Parts I and II feel like a complete unit which mirrors and interrogates its own best elements in interesting fashion throughout. There were reasons for those stories which informed and developed the characters (especially the character of Marty for, as much as Doc makes the storylines possible, Back to the Future is Marty’s story). By contrast, Part III’s visit to the Old West often feels like it exists because, hey, westerns are a thing, right? To me it has always felt forced; it feels like a generic time travel story and not a Back to the Future story.

***

“The way I see it, if you’re gonna build a time machine into a car, why not do it with some style?”

In the week leading up to Back to the Future Day I had (speaking of twenty-first century platforms unimagined by BTTF II) a twitter discussion with @NIBunker. It grew out of a joke I made about the disposal at sea of material from the DeLorean factory outside Belfast (“What if all those DeLorean chassis rusting at the bottom of the Irish Sea are really failed time travel attempts…?”). @NIBunker clarified for me that “they are actually the moulds used to stamp the doors and body panels”. As they explained: “I was part of a group of DeLorean owners who tried to buy them back in 2003. We had a full survey done by a dive team. Sadly they had become too eroded to ever be used again which was our original intention. They are still down there”.

@NIBunker was also kind enough to share some photos related to this. The first shows a scene from the original dumping of the gullwing mould dies, the second – haunting and beautiful – shows what the same die looks like today.

While it is sad to see what is left of the DeLorean dream reduced to just “expensive lobster pot weights”, at least the car lives on in our imaginations, and this in no small part on account of Back to the Future. For outside of the DeLorean owners’ community, the first things most people think of when one mentions the car are Marty, Doc, and their adventures. And this despite the fact that the DeLorean Motor Company was itself history before the first film was even made. Testament, maybe, to the fact that, while one can always try to predict the future, one never knows what is going to be important to it?

__

Other posts you may find of interest: